The Man Who Sired Pecos Bill

Belly up to the bar with Tex O'Riley

A sub-set of folklore is the folk character, figures like Paul Bunyan, Mike Fink and a fellow with Texas roots, Pecos Bill.

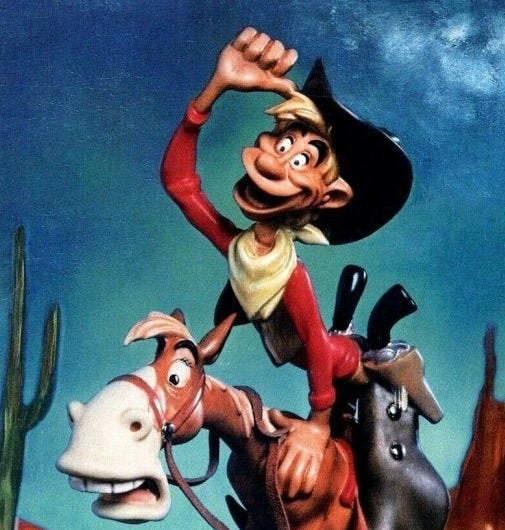

Baby Boomers will recall that Uncle Walt Disney turned Pecos Bill into a cartoon character, but Ole Bill’s older than that mouse in Disney’s first successful animation, Steamboat Willie. Later the character became a bit better known…