The October Barrel

That winter of 1905, seven-year-old Helen Viola Anderson did not grasp that the U.S. stood on the brink of a financial crisis later known as the Panic of 1906. All the San Angelo girl cared about was that her daddy had just died.

On a cold, rainy day only a week or so before, a big load of merchandise had arrived at the March Brothers General Store on Beauregard street, the West Texas city’s principal east-west thoroughfare. That’s where her 51-year-old father worked and no matter the bad weather, he insisted on supervising the wagon’s unloading.

Richard A. Anderson caught a cold which developed into pneumonia. Back then doctors called it galloping consumption and the disease lived up to its name. He died on January 30 and they buried him in Fairmount Cemetery.

“He was a kind and gentle man and we really depended on him,” Helen remembered a near lifetime later, “but Mama and I had to keep going, and we did.”

While Helen attended grade school, Minta Gafford Anderson supported them in the midst of a growing national money shortage by sewing and taking in boarders.

Across the state, young Helen’s maternal aunt Lizzie Gafford Kincaid and her husband Jim struggled to keep their dry goods store open in the little town of Lindale, north of Tyler. One of their friendly competitors had already declared bankruptcy.

“Mama and Aunt Lizzie were very close,” Helen recalled, “but Mama didn’t have much use for Uncle Jim, who fought for the Union in the Civil War. Mama’s family’s farm in Mississippi had been destroyed by Yankees and more than 40 years hadn’t dulled her memory.”

When school let out that summer, the new widow and her daughter packed their travel trunk and took the train to East Texas. While her mother spent time with her sister, visiting, sewing and helping with the annual canning, Helen made friends with the daughter of the man who owned the hotel adjacent to the railroad tracks.

They stayed in Lindale most of the summer, finally making the long train ride back to San Angelo in time for the start of school. Helen missed her new friend, her aunt and uncle and being able to spend time in their store, which sold everything from candy to coffins.

One day that October of 1905, Helen took her time coming home from school. She only hurried when walking through the old cemetery, where they had been digging up graves to make room for a new high school. Jumping over the open graves, she tried not to notice the assorted tarnished coffin handles and leather shoe heels in the piles of dirt.

“Mama was a little put out with me when I finally got home,” she recalled.

Then Helen noticed a large wooden barrel in the middle of their small kitchen. She assumed it held sugar.

“Mama made a lot of preserves, but I couldn’t understand why she would need a whole barrel of sugar,” she said. “Mama pried the boards off the top and I scrambled up on a chair to look inside. All I saw was peanuts.”

The arrival of a barrel of peanuts seemed even more incomprehensible. Her mother could barely afford basic staples, certainly not a luxury like goobers.

“I was still puzzling over it when she fished inside and pulled out an apron,” Helen said. “Her next thrust produced a sack she handed to me. It was my favorite candy. Mama told me to help and my first dip brought out a comb and brush Mama said I could have.”

Finally, Helen understood. Aunt Lizzie and Uncle Jim had sent them a treasure chest in a barrel. It held notions and knickknacks, clothing, buttons, lace, powder jars, writing tablets for school, pencils, dime novels, fruit, preserves, sweet potatoes, ribbon cane, and persimmons – a veritable general store packed in peanuts.

Nothing went to waste. Helen’s mother roasted the peanuts and used the barrel staves as kindling for their kitchen stove or to patch up the back yard chicken coup.

“Every October we got our barrel from Aunt Lizzie and Uncle Jim,” Helen recalled. “Mama never had much money, but the October Barrel wasn’t charity. It was just understood back then that people had to help people. I don’t know how many times Mama got called out in the middle of the night when someone was sick, dead or having a baby.”

Of course, Minta did things for her sister, too. She even sewed for her Yankee brother-in-law.

The last October Barrel came in 1916.

“By that time,” Helen said, “I was married and pretty soon after that barrel came, my husband got a job with a newspaper in Fort Worth and we moved. Not long after, Uncle Jim and Aunt Lizzie sold their store and came back to San Angelo.”

Helen never understood why her aunt and uncle chose to ship the barrel in October instead of nearer Christmas, but she knew how much it meant to a widow and a suddenly fatherless girl.

For the rest of her long life, especially when the days got shorter and the weather turned cooler, my late grandmother remembered the October Barrel and what it taught her about giving.

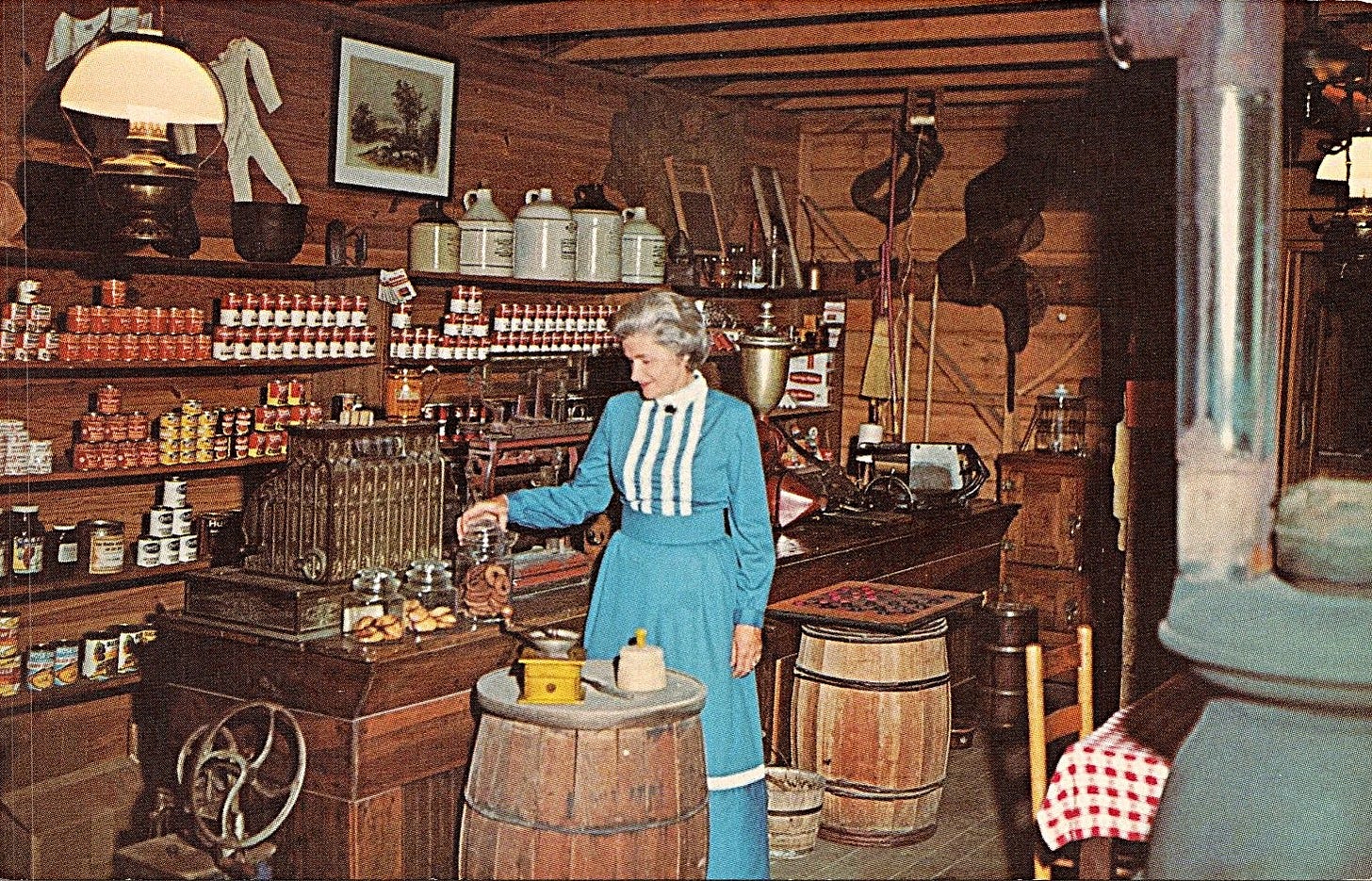

About the illustration: This image is from a vintage

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mike Cox's Texas Magazine to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.