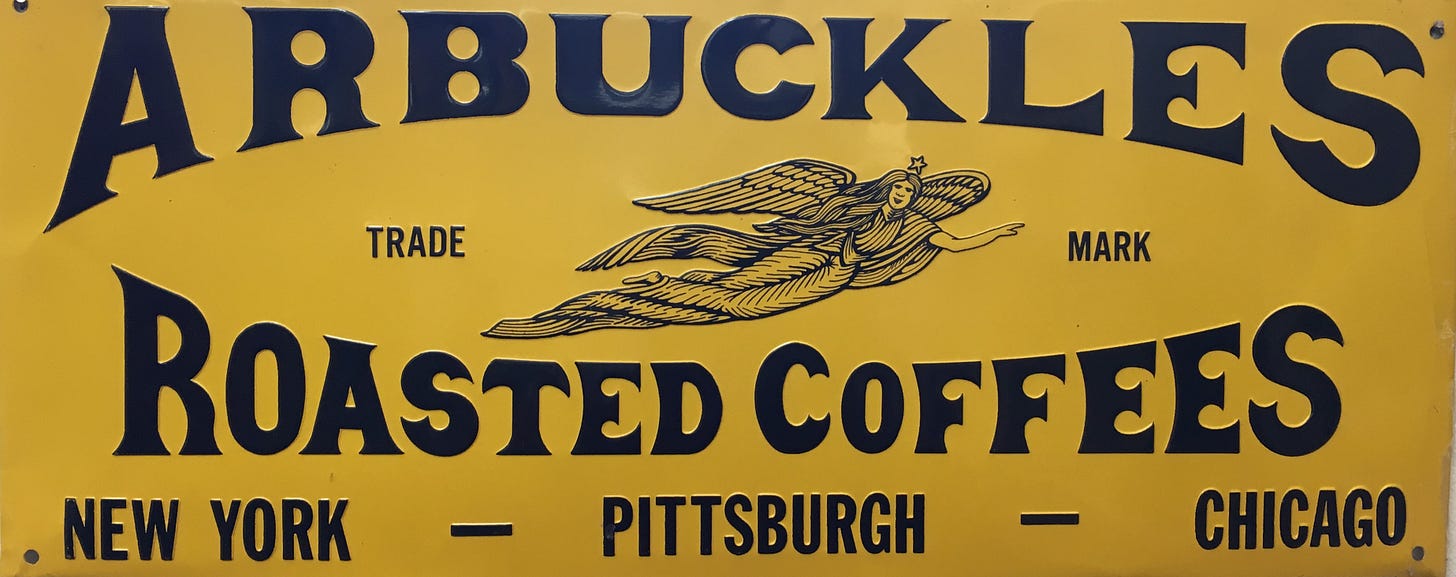

Time for an Arbuckles' Break

The Coffee that Won the West

The Coffee that Won the West" actually came from the East coast.

And no, the company that roasted and packaged the coffee beans that helped fuel Manifest Destiny did not have a nine-letter name beginning with "S." (Hint: Starbucks.) The brand that helped western types get up in the morning and stay at it during the day and even into the night was Arbuckl…